Ottoman Rule (1517-1917)

Following the Ottoman conquest in 1517, the Land was divided into four districts, attached administratively to the province of Damascus and ruled from Istanbul. At the outset of the Ottoman era, some 1,000 Jewish families lived in the country, mainly in Jerusalem, Nablus (Shechem), Hebron, Gaza, Safed (Tzfat) and the villages of Galilee. The community was comprised of descendants of Jews who had always lived in the Land, as well as immigrants from North Africa and Europe.

Orderly government, until the death (1566) of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, brought improvements and stimulated Jewish immigration. Some newcomers settled in Jerusalem, but the majority went to Safed where, by the mid-16th century, the Jewish population had risen to about 10,000, and the town had become a thriving textile center as well as the focus of intense intellectual activity.

During this period, the study of Kabbala (Jewish mysticism) flourished, and contemporary clarifications of Jewish law, as codified in the Shulhan Arukh, spread throughout the Diaspora from the houses of study in Safed.

With a gradual decline in the quality of Ottoman rule, the country suffered widespread neglect. By the end of the 18th century, much of the Land was owned by absentee landlords and leased to impoverished tenant farmers, and taxation was as crippling as it was capricious. The great forests of Galilee and the Carmel mountain range were denuded of trees; swamp and desert encroached on agricultural land.

The 19th century saw medieval backwardness gradually give way to the first signs of progress, with various Western powers jockeying for position, often through missionary activities. British, French, and American scholars launched studies of biblical archeology; Britain, France, Russia, Austria, and the United States opened consulates in Jerusalem. Steamships began to ply regular routes to and from Europe; postal and telegraphic connections were installed; the first road connecting Jerusalem and Jaffa was built. The Land's rebirth as a crossroads for commerce of three continents was accelerated by the opening of the Suez Canal.

Consequently, the situation of the country's Jews slowly improved, and their numbers increased substantially. By mid-century, overcrowded conditions within the walled city of Jerusalem motivated the Jews to build the first neighborhood outside the walls (1860) and, in the next quarter century, to add seven more, forming the nucleus of the new city. By 1870, Jerusalem had an overall Jewish majority. Land for farming was purchased throughout the country; new rural settlements were established; and the Hebrew language, long restricted to liturgy and literature, was revived. The stage was set for the founding of the Zionist movement.

Zionism, the national liberation movement of the Jewish people, derives its name from the word "Zion", the traditional synonym for Jerusalem and the Land of Israel. The idea of Zionism - the redemption of the Jewish people in its ancestral homeland - is rooted in the continuous longing for and deep attachment to the Land of Israel, which have been an inherent part of Jewish existence in the Diaspora through the centuries.

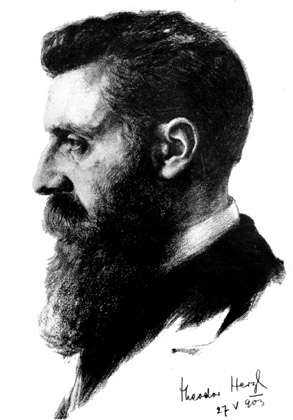

Political Zionism emerged in response to continued oppression and persecution of Jews in Eastern Europe and increasing disillusionment with the emancipation in Western Europe, which had neither put an end to discrimination nor led to the integration of Jews into local societies. It found formal expression in the establishment of the Zionist Organization (1897) at the First Zionist Congress, convened by Theodor Herzl in Basel, Switzerland. The Zionist movement's program contained both ideological and practical elements aimed at promoting the return of Jews to the Land; facilitating the social, cultural, economic, and political revival of Jewish national life; and attaining an internationally recognized, legally secured home for the Jewish people in its historic homeland, where Jews would be free from persecution and able to develop their own lives and identity.

Inspired by Zionist ideology, two major influxes of Jews from Eastern Europe arrived in the country at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries. Resolved to restore their homeland by tilling the soil, these pioneers reclaimed barren fields, built new settlements and laid the foundations for what would become a thriving agricultural economy.

The new arrivals faced extremely harsh conditions: the attitude of the Ottoman administration was hostile and oppressive; communications and transportation were rudimentary and insecure; swamps bred deadly malaria; and the soil had suffered from centuries of neglect. Land purchases were restricted, and construction was banned without a special permit obtainable only in Istanbul. While these difficulties hampered the country's development, they did not stop it. At the outbreak of World War I (1914), the Jewish population in the Land numbered 85,000, as compared to 5,000 in the early 1500s.

In December 1917, British forces under the command of General Allenby entered Jerusalem, ending 400 years of Ottoman rule. The Jewish Legion, with three battalions comprising thousands of Jewish volunteers, was an integral unit of the British army.

Theodor Herzl (Central Zionist Archives) Theodor Herzl (Central Zionist Archives) |