Indian conglomerate puts its cash in future Israeli inventions

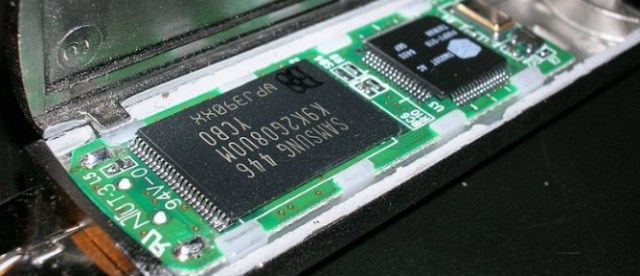

Technology licensed from Ramot provides the advanced error correcting and digital signal-processing controller inside flash memory chips. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Why did a multibillion-dollar Indian company invest $5 million to kick-start the Technology Innovation Momentum Fund at Tel Aviv University’s Ramot technology transfer company?

It’s simple: Starting with the algorithm for error correction code for flash memory – one of the patents filed by Ramot and now inside billions of dollars worth of SanDisk products – Tel Aviv University (TAU) is a powerhouse for the sort of innovation India’s Tata Industries wants to utilize.

“This is our attempt to scout Israeli technology more deeply,” said Tata Industries’ Rameshwar Jamwal at the April 30 announcement.

“Major corporations are facing increasing competition, and they are rarely investing in basic research,” explains Ramot CEO Shlomo Nimrodi. “As a result, they are all trying to figure out where to get the next big thing. They can go to young companies, but that world has its own challenges in raising money. That leaves academic institutions as the source of groundbreaking innovation.”

International and national grants enable TAU to invest more than $150 million in R&D every year, making it the largest research institution in Israel. About half of its 30,000 students are involved in research across a wide spectrum of disciplines. That translates to 1,800 research projects going on at any given time, encompassing everything from brain science to cyber security.

Over the past couple of decades, Ramot has nurtured thousands of patents. Nearly 600 are active patent families, about a third of them licensed to partner companies such as GM, Microsoft, Johnson & Johnson, Ford, Pfizer and Google and nearly 100 more. Forty of them were licensed to Israeli startups.

Nimrodi says that the new Technology Innovation Momentum Fund is meant to help bridge the gap between early-stage innovation and commercialization – “crossing the valley of death,” as he calls it – for inventions in pharmaceuticals and healthcare, clean-tech and environmental, engineering and software.

That valley is dangerous because many promising technologies are either commercialized too soon or too cheaply, leaving the inventors and their institutions high and dry. Momentum Fund managers will identify worthy ideas, bring them to the right stage and then shop around for the right business partner to commercialize them.

Flash memory, mouthwash, scanners

Six products licensed through Ramot are already in the market.

Probably the most famous one, patented in 2004, was Prof. Litsyn Simon’s significant contribution to the X4 advanced error correcting and digital signal processing technology that made the flash memory chip possible.

In 1989, TAU Prof Mel Rosenberg patented a two-phase mouthwash technology through Ramot. In 1997, this technology went into a new Blistex product, Dentyl mouthwash, which today captures a 25% market share in the UK.

The technology in NurOwn, the BrainStorm Cell Therapeutics experimental device for treating neurodegenerative diseases, also comes out of TAU. And so does the expertise behind Motorola’s ER barcode scanners, Polymicro’s optical fibers and Lipimix eye medication.

Tata Industries’ Corporate Vice President and Secretary Sriram S with Ramot CEO Shlomo Nimrodi at the April 30 investment announcement. Photo courtesy of Tata

Currently in the pipeline are a wide range of ideas. Some are geared to treating diseases such as ALS and cancer. Among many others are medical devices, new types of fuel cells and flash-flood prediction software.

Projects that are likely candidates for the Momentum Fund include a muscle cell therapy for treating ALS; a novel drug against bone cancer; an automatic system for the elderly to detect falls in the home; nano-antennas for solar energy harvesting; a wound-healing cream; a special herbicide; cyber-protection software; optical chips and many more.

“Ramot gets the technology in the middle stage, when a patent exists but the product is not yet validated. The Momentum Fund will deal with how to get to the final stages. I don’t think any other academic institution in Israel, or the world, has anything similar,” notes Nimrodi. “It’s an innovative idea in itself.”

Fits Tata’s innovation strategy

Obviously, the leaders of Mumbai-based Tata Industries agree.

This company initiates and promotes ventures in sectors including control systems, information technology, financial services, auto components, advanced materials, telecom hardware and telecommunication services for the huge Indian conglomerate Tata Group. The Momentum Fund outlay is Tata’s first major investment in Israel.

The university is now in the process of securing an additional $15 million for the fund from a variety of sources.

“When we sat down last year to structure this, we felt we needed to find strategic partner to anchor the fund,” says Nimrodi, who entered Ramot around the same time, following a long career in high-tech in Israel and the United States.

“We wanted a company with a diversified portfolio to match the wide range of technologies that we have at TAU; we wanted a global company with scale that is growing fast; and since this isn’t a venture capital fund, we looked for a company in the East because we believe these markets are key. It was then clear that India was a target for us.”

Taking advantage of ties already established through India-Israel Forum conferences established five years ago by former TAU Executive Dr. Gary Sussman, Nimrodi zeroed in on the best potential partner.

“Tata fits the description perfectly. They increased revenues from $20 billion to $100 billion in five years and they’re going toward $500 billion in the next 10 years,” says Nimrodi.

A Tata delegation of 13 scientists came to TAU to see more than 70 technologies in the process of evaluation. “They concluded that this is a structure that would fit well with their innovation strategy,” says Nimrodi. “They get access to a top research institution, promising innovation on a right-of-first-opportunity basis; and a good financial investment.”

Technology transfer has substantial income potential. Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science, for example, collects about $300 million in annual revenues from royalties on technologies licensed out over the past 13 years.

The revenue-sharing model at Ramot channels 40 percent to inventors, 40% to TAU and 20% back to the inventor’s lab.