By Avigayil Kadesh

Brain injury is a hot topic due to growing evidence that even mild trauma suffered in contact sports can have severe consequences. Yet the search is still on for effective medical and cognitive treatments for patients with a brain injury.

Now there is news from Israel on two significant advances, one for assessing the injury faster and better; the other for helping the brain’s rehabilitation process.

Dr. Alon Friedman’s team at the Brain Imaging Research Center at Israel’s Ben-Gurion University and its affiliated Soroka University Medical Center in Beersheva devised “dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging” (DCE-MRI), a new diagnostic tool for visualizing and assessing the types of head injuries commonly encountered in contact sports such as American football and hockey.

“Until now, there wasn’t a diagnostic capability to identify mild brain injury early after the trauma,” said Friedman. “In the NFL [National Football League], other professional sports and especially school sports, concern has grown about the long-term neuropsychiatric consequences of repeated mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) and specifically sports-related concussive and sub-concussive head impacts.”

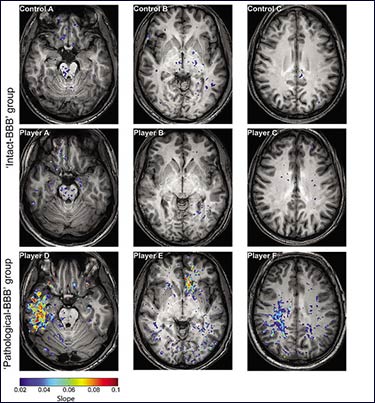

Sixteen members of Black Swarm, Israel’s professional American football team, as well as a control group of 13 track-and-field athletes from BGU, were examined using DCE-MRI. The technology, invented by BGU doctoral candidates Itai Weissberg and Ronel Veksler, is uniquely capable of generating detailed brain maps showing regions with abnormal vasculature -- leaking blood vessels in the blood-brain barrier (BBB).

Forty percent of the examined football players with unreported concussions had evidence of “leaky BBB” compared to 8.3 percent of the control athletes.

Friedman explained that the BBB is composed of proteins, membranes and other materials that protect the brain by preventing many dangerous substances from penetrating.

“The group of 29 volunteers was clearly differentiated into an intact-BBB group and a pathological-BBB group,” Friedman said. “This showed a clear association between football and increased risk for BBB pathology that we couldn’t see before.”

Friedman's group and other medical researchers are hoping to develop drugs to repair a damaged BBB and possibly prevent Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological diseases in some patients.

Images from the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev JAMA Neurology studyThe

results of the study were published in JAMA Neurology and could help physicians in the decision-making process regarding treatment and when an athlete may return to the playing field.

“Generally, players return to the game long before the brain’s physical healing is complete, which could exacerbate the possibility of brain damage later in life,” said Friedman, who researches the role of a damaged BBB in brain dysfunction and degeneration.

Enhanced environment enhances healing

The publication of the BGU study on DCE-MRI came soon after a Tel Aviv University study published in

Behavioural Brain Research showing that an enhanced environment may speed healing in mTBI patients.

Using a model of mTBI in mice, a team headed by Prof. Chaim G. Pick of Tel Aviv University’s Sagol School of Neuroscience and Sackler Faculty of Medicine put one group of the mice into standard cages, while they moved a second group to larger cages outfitted with additional stimuli, running wheels, food and water.

The researchers then observed differences in the mice's level of functioning in each environment. They measured results with the help of the Novel Object Recognition task, in which mice exhibit varying levels of curiosity about new objects placed in their cages and run different mazes to establish navigation abilities.

The behavioral and cognitive evaluation showed that the mice exposed to the enriched environment showed a marked improvement in recovery from brain injuries.

"We have shown that just six weeks in an enriched environment can help animals recover from cognitive dysfunctions after traumatic brain injury," Pick said.

Assuming that the same phenomenon happens in people, the Israeli study suggests that it’s worth trying an enriched environment to minimize long-term damage.

"Possible clinical implications indicate the importance of adapting elements of enriched environments to humans, such as prolonged and intensive physical activity, possibly combined with intensive cognitive stimulation,” Pick said.

“Through proper exercise, stimuli and diet, we can improve a patient's condition. No one is promising a cure, but now we have evidence that this can help."

The consequences of traumatic brain injury -- memory loss, difficulty concentrating, depression, apathy, anxiety and personality changes -- sometimes do not surface until years after the trauma, Pick added.

"In the majority of cases, doctors determine minimal damage according to the symptoms that appear over a very short period of monitoring — just 30 minutes. In 85 percent of cases, this is accurate, but in 15% of cases, a cascade of serious damage has just begun, and we don't really know why. But this is what we are trying to figure out."