By Avigayil Kadesh

Most shelters for teenage runaways don’t look like Israel’s Shanti House.

Perhaps that is because this “warm home for youth at risk” was not planned to be what it is today – two locations saving thousands of teens every year from the streets -- and it was not planned by professionals or government officials.

It began with a teen herself in a desperate situation. Mariuma Klein was born in New York in 1964. By age 14, she was living on the streets of Boston. At 15, she was sent to a boarding school in Israel, and at 17 she was traumatized by a brutal sexual assault.

“I was a kid who went through all the things that the kids we accept in Shanti House go through: neglected, sexually abused, living in the streets,” she says. Yet she continued on to military service and at 19 was sharing a home with the man who would father her three daughters.

On Friday nights, the couple began taking in teens from the streets of Tel Aviv for a traditional Shabbat dinner scrounged up from leftovers collected at the Carmel Market. Tel Aviv is a magnet for Israeli runaways, a bustling city in which they can evade whatever they’re running from.

“From Friday to Friday, there were so many children stuck with no place to eat or sleep,” she recalls. “One girl said she got raped and I was the first one she told, and I told her I also got raped. In this moment, I understood this is my destiny.”

Though Klein went on to earn a college degree in psychodrama, this came much later.

“My degree is 30,000 children,” says Klein, citing the approximate number of teens she has taken in over 29 years. In 2000, she received the President's Award for Volunteerism and in 2007 an Honorary Citizen's Merit Award from the municipality of Tel Aviv-Jaffa.

‘The walls hug you’

In 1984, after a year of Friday night dinners, Klein and her partner transformed their house into living quarters for runaways. One of the girls remarked that she felt “shanti” there, using a Sanskrit word for tranquility.

Spontaneously, another teen wrote “Welcome to Shanti House” in spray paint on the wall. And so it remained.

In 2001, Shanti House moved to its present rented site in the Neveh Tzedek neighborhood of South Tel Aviv. Eight years later, the Shanti House Association opened Desert Shanti House Youth Village in the Negev between Sde Boker and Mitzpeh Ramon, with the help of Ramat Hanegev Regional Council Mayor Shmuel Rifman, the Rashi Foundation and individual donors.

Over the years, Klein developed and honed a unique method for treating at-risk youth. Organizations that work with runaways in cities in Australia, Germany, Mexico and elsewhere regularly invite her to teach them her approach, and she’s currently writing a book about it.

“Shanti House is unique in the world,” she says. “First, it’s a home. When you go inside, the walls hug you. Second, you have to choose to be here. If you don’t choose to be here, whether you’re referred by a court or come from the street, you’ll go somewhere else. Usually when you’re sent somewhere you have no choice. But I believe children who have been victimized have to stand up and say, ‘I choose differently.’”

Shanti House is the only institution of its kind in Israel that takes in youth ages 14-21 every day of the year, 24/7, regardless of religion, race or gender. Other refuges for youth-at-risk do not take anyone over 18.

“Runaways are in two groups,” Klein explains. “The first group are those who don’t really want to run away – usually between 14 and 17 -- and if they don’t get to us they are in danger on the street. We get them back home in 24 hours to one week. We make a bridge between them and their parents, providing professional mediation and guidance.”

Everything your own child gets

Teens in the second group, comprising 75 percent of the clientele at both locations, stay for a month or more. Some find Shanti House through word of mouth; others are referred by social services or juvenile courts.

“They come from all levels of society: very rich to very poor, religious, not religious, Russians, Ethiopians, Bedouins, Druze. For them, we are their last hope. They come from backgrounds of sex abuse, violence or neglect. They are lone soldiers, orphans or children whose parents can’t afford to support them or kicked them out of the house,” she relates.

“These children are the hardest cases of all. They feel rejected day by day; it’s a kind of death,” says Klein, who also sponsors drug-, alcohol- and violence-prevention programs every year for thousands of at-risk youth throughout Israel.

Her objective is that 90% of the youth in this group will be able to financially support themselves before leaving Shanti House, will not turn to drugs or prostitution, will integrate into academic or military structures and will learn to take responsibility for their actions by finding what she calls their inner control center.

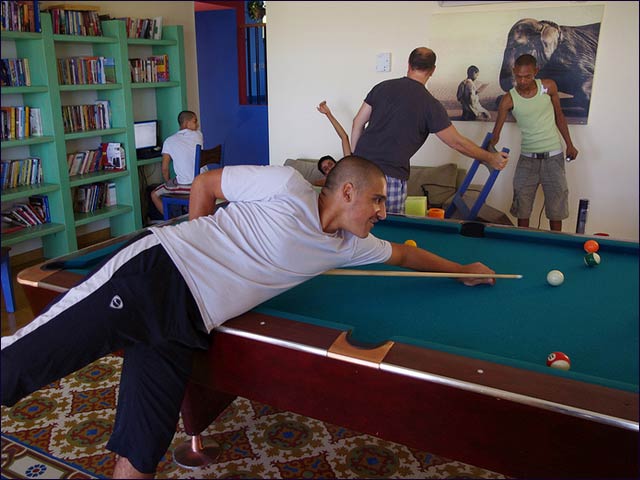

Young men at Shanti House in the NegevA unique therapeutic model, dubbed “Shantherapy,” includes classes, vocational training, enrichment activities, traditional and alternative therapies encompassing 12 Steps, Reiki, agriculture and animal therapy, drumming, drama and one-on-one counseling, among others. The program is personalized for each child.

Shantherapy includes community volunteering. “Giving is part of the therapeutic process and it distracts them from the painful experiences they went through and encourages them to see that they are able to give to society as equals,” Klein explains. Many of the youngsters’ voluntary activities are joint initiatives with volunteers from the business community.

Cultural events, trips and daily chores are part of the program. Traditional Shabbat dinners – where it all started – continue to be a critical focal point of the family-style living at Shanti House. At the festive table, Klein summarizes the events of the past week and then Shanti House Association Deputy CEO Michael Ben Yosef shares an inspiring parable with a moral.

“The kids get everything here,” Klein says. “They go to school or work, they get three meals a day, they get clothing, doctor visits, money to go on buses, school supplies -- everything your own child gets.”

Desert Shanti, ‘completely out of the box’

Klein, who separated from her children’s father in 2001, spends alternating weeks in the Tel Aviv and Negev locations. Hard as it is to split her time, she felt it was essential to open Desert Shanti.

“In Israel there are currently 330,000 children and youth at risk, 28,000 of them in the country’s south,” she explains. “From Beersheva to Eilat there aren’t many places for welfare.”

Desert Shanti House: Home away from home

Through the regional council, she obtained 133 acres in a secluded location that teens could nevertheless easily reach from across the Negev. “They opened their hearts to me, they gave me land. It was a realization of my dream, but I couldn’t do it without others,” Klein says.

Built to “green” standards, Desert Shanti’s rural setting allows Klein to offer additional means of therapy and rehabilitation such as ecological gardening – and at the same time provides much-needed employment for residents of the south.

“It’s something that has never been done before, not in Israel and not in the world,” she asserts. “It’s completely out of the box.”

Among the unique aspects of Desert Shanti is its large Bedouin-style tent where residents of the house can host guests and share in activities including musical performances, art exhibits and poetry readings.

In 2003, the Shanti House Association produced a book of poems written by some of the teens, Sorry We Were Born. The title poem reads: “I’m sorry for being born, sorry for breathing, sorry for eating, sorry for crying, sorry that I dared to love. Sorry, too, for getting beaten, sorry for only wanting to be hugged. Sorry, really I’m sorry. Sorry for bothering you once more. Sorry.”

Low overhead

The Israeli government provides 20% of the Shanti House Association’s annual budget of $2.2 million, and other Israeli donors help. However, part of Klein’s constant routine is traveling abroad to raise the additional $1.2 million every year. (It’s possible to donate through the Internet site, and contributions in the United States are tax-deductible.)

She fields many requests to open Shanti House branches in Jerusalem and in the north. In theory, she likes this idea because the four locations would cover the whole country. However, she is wary of overstretching her already modest budget at the expense of the two existing locations.

Shanti House Tel Aviv Just 13% of the annual budget goes to administration. “I’m very proud of that,” says Klein. “We keep the overhead very low.” Employees number 30, a few of them former residents.

Klein’s oldest daughter, now studying acting in New York, also worked at Shanti House for a time. Klein says that one of her greatest accomplishments is managing to raise three well-adjusted daughters in the unusual environment of a shelter for runaways – where many of the kids call her “Ema,” Mom.

“My girls are so healthy in their brains and in their souls,” she says. “I am proud that I succeeded as a mother because it might not have happened that way. I feel you cannot be a mother to others if you’re not successful with your own children.”

And just as parents must learn to let their grown children go, Klein is making sure that the social-welfare program she conceived, birthed and raised will continue beyond her.

“I knew I had to take my life project and teach others how to take it over when I’m no longer here,” she says. “Sometimes when you grow such a project you forget to let it go, and let others also make it theirs, and the project dies with you.”