By Rivka Borochov

His friends tried Europe and Disneyland. But after a solo pre-army trip to Kenya when he was just 18, Ofir Drori from Tel Aviv decided that Africa was in his blood. As soon as he was released from the Israeli military, Drori headed back in search of adventure and alternative ways of living.

By 2003, he had founded LAGA, the Last Great Ape Organization. His non-governmental organization became the first in Africa to break the cycle of animal poaching and illegal wildlife trade, which starts in Africa with elephants and gorillas but is a globe-spanning problem fueled by demands of the rich and curious.

“Ours is the first wildlife enforcement NGO. We have a new model, one that assists governments to stop the wildlife trade,” says Drori, who was born in 1976.

“The illegal wildlife trade is the major cause for species extinction,” he explains. “We have taken the baseline of zero prosecutions in the West and a very poor record for all of Africa, where corruption is still rampant –– the major obstacle for this illegal trade.”

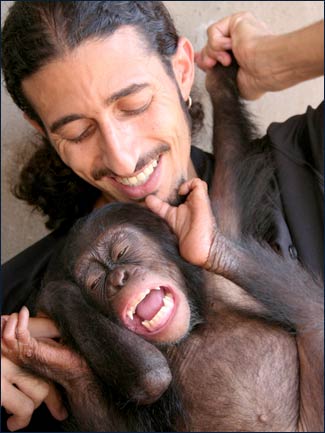

LAGA’s Ofir Drori works to protect animals like this one

LAGA’s Ofir Drori works to protect animals like this oneOn average, one major wildlife trafficker is now convicted and jailed every week in Africa, thanks to Drori and LAGA.

LAGA’s work has become so effective that there have been death threats to Drori and his team, but he sees the bigger picture.

“Wild animal traffickers are big criminals connected to arms smuggling and the drug trade. They are using their money to try and corrupt officials. Now that Africa is taking a step forward in fighting corruption, they are working with our NGO to take on the fight.”

Illegal poaching is lucrative

The first LAGA model was developed in Cameroon 11 years ago, and it is now replicated in Gabon, the Republic of Congo (Brazzaville), Central African Republic, Togo and Guinea (Conakry), with six more African countries on the waiting list for when resources become available. Until LAGA, there was no way to enforce the wildlife laws in these African countries.

Who’s driving the illegal trade?

While the Chinese market is hungry for ivory tusks, and people in Arabian Gulf countries love to show their guests live gorillas living at home, virtually every Western country is also guilty, whether it’s an exotic pet parakeet or a meal of lion meat.

Drori doesn’t place the blame on Africa, but on the organized crime rings that control a massive network of local poachers who trap and kill for daily sustenance.

Illegal wildlife trade for the big guns is a lucrative business –– unless, of course, they are behind bars.

Using local agents, Drori works on the ground in Africa to sniff out and arrest the handlers of a small army of poachers who kill, torture and traffic animals for food, body parts, or as pets.

His agents get a nice bonus if an arrest is made.

In 2012, Drori won one of the most coveted prizes in his field: the World Wildlife Fund for Nature’s Duke of Edinburgh Conservation Medal.

His investigations, sting operations and hiring legal teams to prosecute, as well as media work, he says, has led to the arrest and conviction of 900 animal poachers. This is a victory for African governments and the animals whose lives he has saved.

Human-applied tools for the trade

Born and raised in Tel Aviv in the 1970s, Drori had a pretty unconventional upbringing. By age four, he was allowed to play with glass so that he could experience the pain of getting cut.

“My parents were all about encouraging experience so I could make my own opinion,” he explains.

His preserved science experiments with dissected animal parts were not allowed in the apartment, and frightened the neighbors out in the hall.

Drori spent his junior high and high school years at the alternative Teva School in North Tel Aviv. When his peers were out clubbing or going to bars, he was in nature.

“I was an autodidact, who didn’t like to sit in classrooms. I never had great relations with authority.”

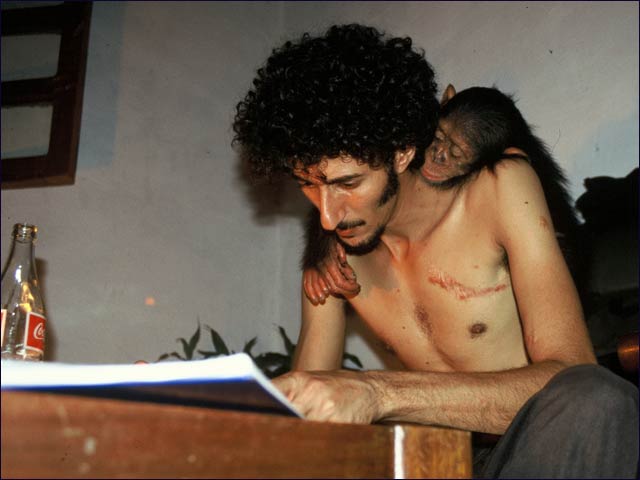

Drori is a product of an unconventional upbringing

Drori is a product of an unconventional upbringingOfir, his first name, also is the name of an ancient African country – the Queen of Sheba’s kingdom. Mesmerized by the stories from his youth that his dad told him, Drori always wanted to see the biblical Ofir for himself. “Sheba described it to King Solomon as a place with diamonds and gold, and precious stones,” he says.

Today Drori is based in Cameroon, where he commands a team of undercover locals outfitted with hidden cameras to infiltrate poaching operations.

Death threats and legal threats pervade their lives, but these don’t keep Drori awake at night. The activist in him presses on while his parents are proud of what he does.

As an activist for animals, Drori also cares about humans. The same tools he uses to save the animals are also applied to those who are arrested. “I don’t want to see those prosecuted rot in jail, but just to make sure that they serve the time they deserve,” he says. LAGA lawyers help ensure those sentenced for animal trafficking are not abused while serving their time.

For Drori, his dreams of Africa have become a self-fulfilling prophecy: “When I went back to Africa after the army, there was no return.”