(Communicated by the Hebrew University Spokesperson)

If you could travel back in time to 100,000 years ago, you’d find yourself living among several different groups of humans, including Modern Humans (those anatomically similar to us), Neanderthals, and Denisovans. We know quite a bit about Neanderthals, thanks to numerous remains found across Europe and Asia. But exactly what our Denisovan relatives might have looked like had been anyone’s guess for a simple reason: the entire collection of Denisovan remains includes three teeth, a pinky bone and a lower jaw. Now, as reported in the scientific journal

Cell, a team led by

Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI) researchers Professor Liran Carmel and Dr. David Gokhman (currently a postdoc at Stanford) has produced reconstructions of these long-lost relatives based on patterns of methylation (chemical changes) in their ancient DNA.

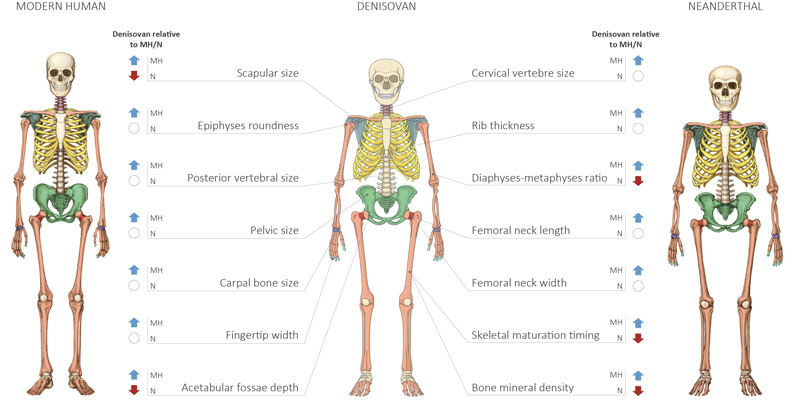

“We provide the first reconstruction of the skeletal anatomy of Denisovans,” says lead author Carmel of HUJI’s Institute of Life Sciences. “In many ways, Denisovans resembled Neanderthals but in some traits they resembled us and in others they were unique.”

Denisovan remains were first discovered in 2008 and have fascinated human evolution researchers ever since. They lived in Siberia and Eastern Asia, and went extinct approximately 50,000 years ago. We don’t yet know why. That said, up to 6% of present-day Melanesians and Aboriginal Australians contain Denisovan DNA. Further, Denisovan DNA likely contributed to modern Tibetans’ ability to live in high altitudes and to Inuits’ ability to withstand freezing temperatures.

Overall, Carmel and his team identified 56 anatomical features in which Denisovans differ from modern humans and/or Neanderthals, 34 of them in the skull. For example, the Denisovan’s skull was probably wider than that of modern humans’ or Neanderthals’. They likely also had a longer dental arch and no chin.

Anatomical Comparison of Modern Humans, Neanderthals and Denisovan Skeletons. Image courtesy Hebrew University/Maayan Harel.

Anatomical Comparison of Modern Humans, Neanderthals and Denisovan Skeletons. Image courtesy Hebrew University/Maayan Harel.

The researchers came to these conclusions after three years of intense work studying DNA methylation maps. DNA methylation refers to chemical modifications that affect a gene’s activity but not its underlying DNA sequence. The researchers first compared DNA methylation patterns among the three human groups to find regions in the genome that were differentially methylated. Next, they looked for evidence about what those differences might mean for anatomical features—based on what’s known about human disorders in which those same genes lose their function.

“In doing so, we got a prediction as to what skeletal parts are affected by differential regulation of each gene and in what direction that skeletal part would change—for example, a longer or shorter femur bone,” Dr. Gokhman explained.

To test this ground-breaking method, the researchers applied it to two species whose anatomy is known: the Neanderthal and the chimpanzee. They found that roughly 85% of their trait reconstructions were accurate in predicting which traits diverged and in which direction they diverged. Then, they applied this method to the Denisovan and were able to produce the first reconstructed anatomical profile of the mysterious Denisovan.

As for the accuracy of their Denisovan profile, Carmel shared, “One of the most exciting moments happened a few weeks after we sent our paper to peer-review. Scientists had discovered a Denisovan jawbone! We quickly compared this bone to our predictions and found that it matched perfectly. Without even planning on it, we received independent confirmation of our ability to reconstruct whole anatomical profiles using DNA that we extracted from a single fingertip.”

In their

Cell paper, Carmel and his colleagues predict many Denisovan traits that resemble Neanderthals’, such as a sloping forehead, long face and large pelvis, and others that are unique among humans, for example, a large dental arch and very wide skull. Do these traits shed light on the Denisovan lifestyle? Could they explain how Denisovans survived the extreme cold of Siberia?

“There is still a long way to go to answer these questions but our study sheds light on how Denisovans adapted to their environment and highlights traits that are unique to modern humans and which separate us from these other, now extinct, human groups,” Carmel concluded.

Professors Eran Meshorer from the Hebrew University, Yoel Rak from Tel Aviv University, and Tomas Marques-Bonet from Barcelona’s Institute of Evolutionary Biology (UPF-CSIC) contributed to this research.