By Avigayil Kadesh

People – Including at-risk youth, minorities, new immigrants, trauma victims and special-needs groups – work with a specially trained Ma’aleh therapist and filmmaker team, learning to create films to explore their stories and issues, and discovering what their stories mean to them.

“Do a Google search on ‘video therapy,’ and you’ll come up with sites about documenting a therapeutic process on video,” says Yarden Kerem, who has headed, shaped and expanded the Video Therapy Center since her arrival at Ma’aleh three years ago.

“We use this instrument in a different manner – as a creative art instrument,” she says.

At the heart of each personal documentary -- an “I movie” -- stands the creator telling his or her life story through video art.

Film enables self-discovery

“We find that this instrument is highly amazing,” says Kerem, a private clinician who has a master’s in fine arts from Tel Aviv University and is completing a second master’s there in interdisciplinary art.. “Our therapy center handles groups who go through a process of 24 weekly sessions, where we work together with other therapeutic instruments such as therapy through video – watching films and holding therapeutic discussions after the screening.”

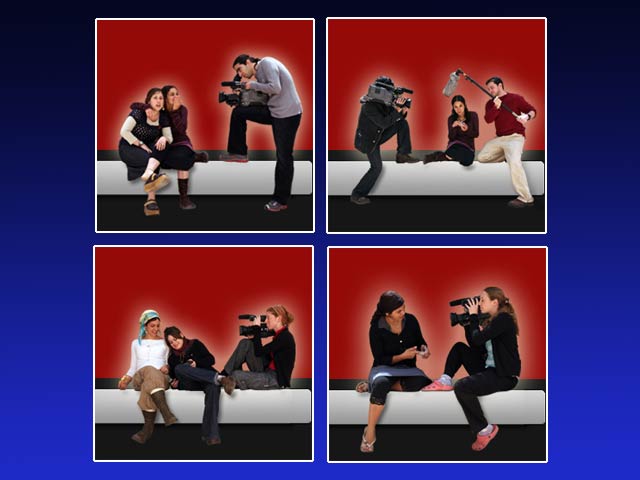

Ma’aleh students at work Ma’aleh has recently worked with five Jerusalem teenagers who each experienced the death of a parent; Arab youths exploring the forced marriage of a 17-year-old girl in their social circle; a gang of teenage boys accused of attacking an injured person whom they were actually attempting to help; and a girl who, after being removed from her dysfunctional home by the court, runs away from her group home, gets assaulted on the streets and has a pivotal encounter with a Holocaust survivor.

“From one meeting to another, from one exercise to another and through discussions of film issues such as what is an image, what is a creative event, how does one express conflict in cinema, the group raises from within itself its united voice – the subject on which it wants to make a short action film.”

The scriptwriting and filmmaking process enables people in therapy to express themselves and their inner world in an unusual way. Viewing the finished product leads them to discover things that may not have been apparent before.

“From each filmed piece, one can move on to working on emotions,” says Kerem. “What existed only in my own private brain, or was my own personal experience, dimly, with no words, unorganized, untreated, assumes a totally different attitude when it is seen on a big screen. It is no longer blurred, but something full of life that I can relate to.”

“The key question is what happens from a therapeutic point of view – or where does the therapy take place in the process of making a film?” Kerem explains.

“There are no written theories about this because therapy through films has not been researched. There are virtually no academic sources. We hope that our work will provide the theoretic foundation to understand what makes this process so very powerful from a therapeutic aspect.”

On June 19, 2014, Ma’aleh hosted its fourth annual conference on video therapy.

Film as a mirror of the soul

Kerem says participants in video therapy report feeling greater self-confidence and a newfound sense of calm and serenity at the conclusion of the project.

“We do not hand out questionnaires at the beginning, middle and end of the year in order to note the change. But to those involved in this work, it is evident that something good is happening. We work from within our guts; the theory will come later.”

Kerem continues: “Since each film expresses the worldview of the maker, each piece of filmed reality can be used as an instrument for therapy. From each filmed piece, one can move on to working on emotions. Hopefully, once the filmed material reaches the therapy stage, it will assume vast meaning and significance.”

In the case of groups, such as the orphaned teens in Jerusalem, the therapeutic video expresses the voice of the group in the scriptwriting process and in the on-screen action, she adds.

Last year, 15 students completed their one-year certification in video therapy at Ma’aleh. One track is offered for credentialed filmmakers and another for certified therapists, getting both up to speed on the dual nature of the approach.

Kerem says there is interest from people in other countries in using this method, which she terms “very powerful.”

“Documentary films, in general, have a lot in common with therapy, because usually they’re about people’s lives,” says producer Ron Ofer, who teaches documentary filmmaking at Ma’aleh’s Video Therapy Center.. “And the director, even if the film is not about himself, has a personal stake in it. There are a lot of psychological aspects to it.”

Kerem explains that in other forms of psychological therapy, “treatment occurs through a relationship created between therapist and patient, or though the interpretation that either of them gives to things. Here, we think that the process occurs due to the ability of cinema to contain fully, and not critically, the personal story. The camera absorbs everything and is never critical.”

Ma’aleh’s task is to train filmmakers to empathize and pay full attention to the patient's story, without interpreting it.

“Through the work of art in itself there is relief,” she says. “Film allows a sense of control over one’s life and the power to rebuild it.”

Cinema introduces two important developments to the therapeutic process, she adds: allowing the subject to give expression to an emotional state and see how it looks, and enabling the subject to share what was formerly a private burden.

“The film is a mirror of the soul that enables looking directly at difficulties and inviting other people to relate to me as a person who is no longer discrete, but a person who is prepared to say, ‘Here, this is me, that is my story.’ Cinema is a long process that allows time to deal with the personal story and with the process that occurs after the film is produced.”