By Avigayil Kadesh

Despite daytime heat and nighttime frost, despite wolves that sometimes steal their dairy goats, despite the lack of neighbors as far as the eye can see, Leah and Gadi Nechimov would not dream of living anywhere but Israel’s Negev Desert.

Same goes for Golan Cohen, a herb farmer in a young Negev village, and vintner Moshe Zohar – in addition to more than 100 Israeli families every year who choose to uproot their city life in favor of a new earthy existence in seemingly the middle of nowhere.

“It’s beautiful here,” says Leah Nechimov. “We wanted to change our atmosphere, and we love the weather, the views, the atmosphere in the Negev. We love the people themselves.”

About 700,000 people, or about eight percent of the Israeli population, live in the Negev, which covers more than half the state of Israel from Beersheva in the north to Eilat in the south. Some 200,000 of them live in the city of Beersheva, the unofficial capital of the Negev. Beersheva is experiencing a business and building boom, and its population is expected to double in the coming years.

A strong Beersheva is good for the little satellite villages and farms popping up around the Negev through the efforts of the Ministry of Negev and Galilee Development, regional councils, and special programs such as the Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael-Jewish National Fund (KKL-JNF) “Blueprint Negev” initiative.

In February, a KKL-JNF housing fair offered information about new opportunities to the slow but steady stream of Israelis (and a few hardy immigrants) wishing to take advantage of economic incentives -- including free or heavily subsidized plots of land -- to follow others blazing a trail in rural living.

Learning the basics

Nechimov and her husband established Naot Farm nine years ago with the help of the Ramat Hanegev Regional Council. They formerly owned a chain of El Gaucho restaurants in central Israel.

“At nearly 40, it was time to fulfill our dream to build a farm from zero,” Nechimov explains. “We decided on goats, to make cheese. We worked on a goat farm near Jerusalem for a few months to learn the basics, and we’re still learning.”

Their herd has grown from 50 to 500, and last year they added sheep to sell for meat. Naot Farm milk, yogurt, soft and hard cheeses are sold in about 65 delis and restaurants in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

Leah Nechimov with her goat yogurtNechimov has laid out a spread of cheeses, fresh breads, olives and marinated cherry tomatoes on the wooden porch of one of the farm’s four guest houses. She reaches into the yard surrounded by rolling brown hills to pluck some lemongrass for tea.

Many Negev newcomers are so eager to share the experience of their surroundings – and to supplement the income their farms provide – that they build rustic bed-and-breakfasts on their property for visitors from far and wide. Though agriculture accounts for 80% of local residents’ livelihood, tourism is the second most important niche.

“A lot of tourists are looking for the spirit of pioneering, and the Negev is one of the few places you can find it,” says Raz Arbel, head of the tourism department for the Ramat Hanegev Regional Council, which encompasses 22 percent of Israel’s land mass -- covering 1.1 million Negev acres from Yeruham to Mitzpeh Ramon, and about 20,000 Jews and Bedouin Arabs.

New definition of ‘pioneering’

Arbel often shows visitors around the 13 villages and 23 farms in his central third of the desert.

“People feel they really are doing something meaningful -- blooming the desert, building their houses on the border of Egypt, struggling with nature and distance and economics.

“What drives them? The second or third word out of their mouths is always ‘pioneering.’ But the translation of pioneering is different today; it’s more about self-fulfillment,” says Arbel. “They are moving south from Tel Aviv for the quality of life, for the high level of education, environmentalism, security and culture. You might think there are fewer opportunities for these things here, but actually that is not true.”

Strawberries growing at the Ramat Hanegev

agricultural R&D stationMuch of the educational, cultural and professional life of this region revolves around Midreshet Sde Boker, a multi-institution education, research and residential hub that includes, among about two dozen institutions, Ben-Gurion University’s Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research and the Ben-Gurion Heritage Institute . This is where the Nechimovs’ youngest son, 11, attends school and meets friends from isolated families like his own.

“The investment per child in the school system is five times more here than in the cities,” says Arbel. Prioritizing education and recreation, even at a high cost per head, helps make the Negev an attractive and affordable alternative.

While most of the new pioneers are secular in outlook, a few religious and mixed secular-religious villages are also developing nicely, according to Arbel.

“Everyone said there was no way religious families would choose the Negev,” he relates. But several pilot religious villages begun a decade or more ago, such as Merhav Am and Sansana, are now buzzing with construction of permanent houses as well as synagogues, community centers and kindergarten structures paid for by donors including the KKL-JNF’s community-building OR Movement.

Alon Badihi, executive director of the JNF Israel Office, reveals that there are hundreds of names on a waiting list for Gvot Bar, a brand-new village near Beersheva planned as an exclusive secular community for about 400 families. It boasts public facilities such as a daycare center and a two-acre park with bike trails. “If we had enough land, we could sell 1,000 [homes],” Badihi says.

Many of the adults moving to Gvot Bar will keep their jobs in Tel Aviv, Rishon LeZion and Rehovot, he adds. “It’s not a far commute and it’s against traffic.” Others may telecommute or seek work in Beersheva, where many new branches of national businesses are opening in addition to existing large employers such as Ben-Gurion University and Soroka Medical Center.

“People are willing to pay the driving time if they have a good community,” says Arbel. “If you design your own community, you can decide what your life will look like.”

Ben-Gurion’s dream

There is still a long way to go before the Negev matches the vision of David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister.

In 1951, Ben Gurion was on the road to Mitzpeh Ramon and noticed a few tents along the road. A group of 13 recently discharged soldiers was establishing a kibbutz here to raise horses and cattle (Sde Boker means “Cowboy Field”). He stopped to speak with the young pioneers, coming away with a determination to join the kibbutz despite his relatively advanced age of 67. His membership application was approved, though only by a slim majority.

Today the kibbutz, including Ben Gurion’s modest house, is a major tourist attraction and displays a new animated film about his passion for populating the Negev. His dream of five million Jewish residents in the Negev predated his own move to Sde Boker.

“In the 1930s, he said three things have to happen for his dream to come true: a massive aliyah of Jews from other countries, peace with our neighbors to the south, and when the density and ecological problems of the center become impossible,” says Ronit Barak, a guide at Sde Boker. “He envisioned three million people working in industry, and two million in agriculture.”

Moshe Zohar in his wine cellarThe way things turned out, agriculture is much more prevalent. The Arava Valley portion of the Negev has 600 farms supplying more than 60 percent of Israel’s exports of fresh vegetables and 10% of ornamentals such as cut flowers.

Support for farmers is key to the region’s ability to attract new residents.

“If you’re looking to be a farmer, we help with water rights, land, loans, training and marketing -- all for free,” says Arbel.

“Not everybody can live in this way, and some of the farms failed but most have been successful. We have 30 places available for very cheap, and the first time we publicized it, 400 families applied. A lot had no clue about agriculture but just wanted more meaning in their lives. A committee chose which would be most likely to succeed.”

Farming the Negev

The 23 small family farms currently dotting Ramat Hanegev all have a say in what kinds of experiments are done at the region’s agricultural R&D center, one of 19 stations around Israel that devise protocols for growing, picking and packing.

There is a plan to build a tourist center at the site, featuring a film and exhibits about the experiments, including the highly successful innovation of feeding vegetables on brackish (salty) water.

“Seventeen years ago, we found brackish aquifers under the ground,” says Arbel. The national water carrier, Mekorot, drilled 18 wells, at a cost of $1 million each, to pump the water to area farms at an attractive price.

“Now it’s our challenge to show them how to use it. Twelve years ago, one of the agronomists found out how to irrigate cherry tomatoes in brackish water, and the result was so amazing in terms of quality and quantity that we went to farmers and said, ‘Stop using expensive freshwater to irrigate. Use brackish water and you’ll see better results and longer shelf life so you can export to far-away countries.’ This was the start of the Desert Sweet brand.”

The prized Desert Sweet cherry tomatoes grow on 2,000 acres in Nitzana, a cluster of villages near the Egyptian border. “We are the only area in Israel that can grow cherry tomatoes for 10 months of the year,” continues Arbel. “One plant can produce a few kilos over that time. We produce 25 tons per quarter acre, while the world average is seven.”

Researchers discovered that olive trees and pomegranates also thrive on brackish water. Now they are attempting to grow additional crops, such as table and wine grapes, strawberries and cotton, on the salty H2O.

The wine grapes have so far not responded well to the salty water, but the agronomists at the station have not given up. “We have nine wineries here, and the farmers would like us to keep trying,” Arbel says.

‘I made everything here with my own two hands’

Moshe Zohar’s Boker Valley Vineyards Farm produces merlot grapes for the large Barkan Wine Cellars . The soil and night temperatures in the Negev are perfect for wine grapes, Arbel explains, and that is why the area is known as the Wine Route from ancient times.

“There is evidence of vineyards here from 2,000 years ago -- Nabatean times -- and all the Nabatean terraces are being reused by today’s farmers.”

Zohar and his wife moved to this patch of land 15 years ago. They sowed their grapes and established a restaurant, which they later closed. Now their main income is from their Desert Lodge guest houses; a party venue in a building designed to look like a wine barrel; and a wine shop.

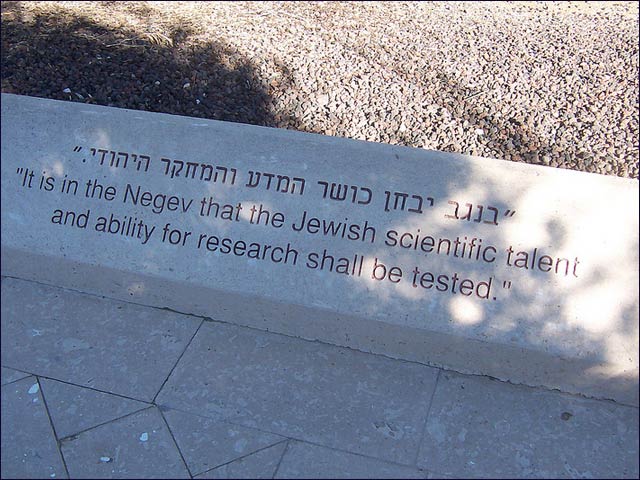

Kibbutz Sde Boker features path markers with

quotations from David Ben-Gurion about settling the Negev“Moshe saw that there was no store here that sells all the local wines from the nine wineries, so he made a wine cellar to do that. People can come and taste, and choose whatever they want. If they buy a bottle he doesn’t charge for the tasting. It’s a great concept.”

Zohar also sells other local produce, such as fresh herbs. The Negev is not an easy place in which to make a living, but he wouldn’t trade it for anything.

“I love the stars at night. I love making something out of nothing,” he says, gesturing toward the living quarters he fashioned from four shipping containers. “I made everything here with my own two hands.”

Herb farmer Golan Cohen, 37, also cannot see himself anywhere else.

“I grew up in Jerusalem, and since I was eight I told my parents I wanted to live in the desert,” Cohen says. “I used to hike a lot in the desert as a youth. It wasn’t even a question for me: After I left the army and traveled to Africa and India, I needed to be in the desert. I like the climate here. Everybody thinks it’s very hot, but it’s not humid so it’s better than most other parts of Israel.”

Six years ago, he and his wife, Noa, were among the first families in Be’er Milka, a new village in Nitzana established by pomegranate and herb farmers. Their Shirat Hamidbar (Song of the Desert) farm raises organic medicinal herbs and table grapes, and offers tours.

The Cohens work closely with the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies and with a medicinal herb research project begun at Jerusalem’s Hadassah Medical Center and continuing at Tufts University in Massachusetts. Volunteers from several countries come to work the farm each year, and tourists are discovering it, too.

Golan Cohen, medicinal herb farmer at Shirat Hamidbar “The idea of the farm was not only agricultural,” Cohen stresses. “We wanted to have the ability to bring people here and show them how to use herbs in their life and how easy it is to grow them even in imperfect conditions.”

Israeli argan oil

The Cohens have a background in permaculture, an agricultural approach that integrates human activity with natural surroundings in order to create efficient self-sustaining ecosystems.

“We spent a year seeing what we could grow in the poor desert soil. The first thing was argan trees from Morocco. We have a huge underground saltwater aquifer watering more than 1,000 trees, and hopefully next summer we will start producing oil,” says Cohen.

While they wait the requisite five or six years for their argan trees to bear fruit, Orly and Yoni Sharir are already producing argan oil at their Orlyya Farm. This rare oil, rich in vitamin E and fatty acids, is coveted for its antiseptic and nutritional properties.

Orly Sharir cracking argan nuts for their precious seedsThe Sharirs met at Kibbutz Sde Boker, where he was a park ranger and she was leading a Birthright tour. After their marriage, while working as shepherds, they became interested in Nabatean agriculture. The farming spot they chose to start their venture in 2003 has a trail of stones carved with Nabatean-era symbols meant to mark the way for ancient travelers.

“In Israel there are five or six other farms growing the argan tree, but we are the first pressing the oil,” says Orly Sharir. “We started with two trees and today we have 400, all organic. The climate here is perfect for them. We imagine in 10 years we’ll have a forest out here with tall trees that don’t need much water.”

Yoni Sharir cracks the nuts by hand, extracting the seeds one at a time. Their five children help press, bottle and package the oil. The crushed seeds are sent out to be made into an exfoliating soap.

In addition to two guest houses, Orlyya Farm offers tours of their operation. “We speak to groups about agriculture and Zionism in the Negev in 2013. People are welcome to come and knock on our door and have tea and cookies. We’re always here for them.”

New communities

The JNF’s Badihi says it is unrealistic to expect large numbers of Israelis and new immigrants to choose the Negev if they have to scale back on their quality of life. So the organization has been investing millions of shekels in projects from landscaping to reservoirs.

One such project is a large new park midway between the cities of Dimona and Eilat, which are separated by 100 miles. Inaugurated in February after five years of planning and construction, the park combines businesses, restaurants and playgrounds. It is situated in the Eilot Regional Council, which reaches from the Red Sea resort city of Eilat up to the little Arava community of Yahel.

“In a year, new houses will be ready in Yahel, but people will not stay there if a woman has to give birth in an ambulance, so we are starting to build a regional medical center in Sapir, the ‘capital’ of the central Arava,” says Badihi.

In the meantime, the JNF is working with Nefesh B’Nefesh, an organization that facilitates aliyah from North America and the UK, to sign up five physicians and their families to form the nucleus of a new Sapir community for doctors, scientific researchers and scholars.

Banking on continued development of Beersheva, the OR Movement is offering 100 plots of land in Carmit, a new village between Beersheva and Arad near Highway 6. “It will be huge,” predicts Badihi. “They’re selling like crazy. In the end, there will be 400 plots. I would guess we’ll be overbooked in a matter of months.”

Once a pilot village for religious families, Sansana is

now moving toward permanent structuresEin Yahav, a farming cooperative that is currently the biggest community in the Arava, is slated for an additional 70 families, half of whom will work in businesses rather than agriculture.

Several of the villages currently being established in the desert are revolutionary in their social outlook.

Not long ago, the Ramat Hanegev Regional Council helped a group of religious and secular young families get started on a new communal living venture that grew out of their experience with the Ayalim Association, founded in 2002 by a group of 20-somethings to promote the development and settlement of the Negev and the Galilee by university students.

Some 700 students are now scattered among 12 Ayalim student villages (half of them in the Negev), receiving government assistance including full scholarships in exchange for 10 weekly hours of community volunteering. After three or four years of living in the periphery, many of the students choose to remain as they start families and careers. “Demand is surprisingly high,” says Arbel.

The KKL-JNF is also investing in programs aimed at keeping residents of established Negev cities like Yeruham, Dimona and Beersheva from migrating northward. Too often, he explains, children in these economically and geographically peripheral areas are taught to define success as relocating to the center.

“We are trying to change that,” says Badihi. “For example, we established a youth house serving ages 16 to 32 in Yeruham that gives a variety of education, leadership and volunteering opportunities. They go to [Ben-Gurion] University and return to Yeruham three times a week to share what they learned. It has been very successful in keeping people here.”

“Our goal is to bring 500,000 people to the Negev,” Badihi concludes. “It’s a long shot, but if you don’t aim high you gain nothing.”