Increasingly, the Technion is opening its doors to wider global involvement.

“A few years ago we launched an

International School of Engineering,” says Shapiro. Studying exclusively in English, students from many different countries can earn a bachelor’s degree in civil and environmental engineering here.

A Technion lecture hall

“Like all universities, we are aiming to be more and more international and encourage post-grads to come here,” Shapiro says. “The partnership with Cornell is part of our internationalization. Israeli academia has a lot to offer, and this tech campus in New York is one way Israel can contribute to the world economy.”

But the school invests most of its resources locally, starting at the grassroots level. Shapiro notes that the Technion has implemented programs to help disadvantaged and minority students to overcome educational and social gaps. For example, the 10-year-old Landa Equal Opportunities Project has successfully prepared many Israeli-Arabs for social and academic integration at the Technion through pre-university preparation and intensive mentoring and tutoring.

The institute also runs several joint regional medical, environmental and water research projects with partners from Arab communities. For example, the

Technion’s Water Research Institute recently completed a multi-year research project on treating wastewater and maximizing its quality and usefulness in agriculture.

“This type of research is aimed at helping all peoples of the region better utilize severely limited water resources, promoting economic growth, quality of life and the environment,” says Shapiro.

Overcoming a shaky start

Today it’s clear that the Technion lived up to Einstein’s hopes, and then some. However, the school’s future success was difficult to envision back then.

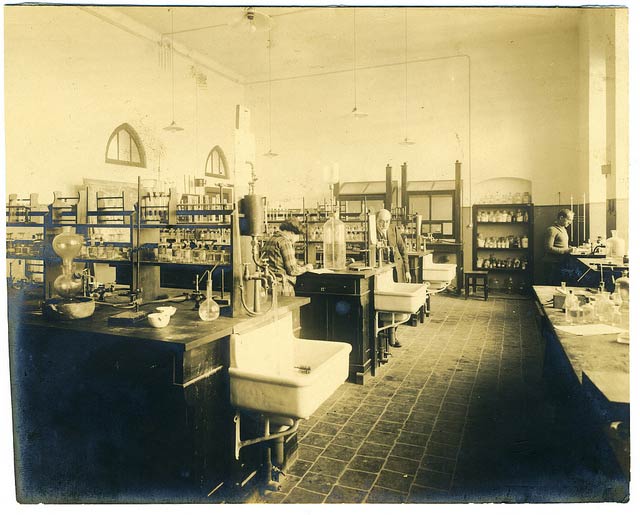

An early lab at the Technion

One of the first problems was deciding on the language of instruction. German was an obvious choice, as it was the language of science, and modern Hebrew was just making its comeback. Yet the proponents for Hebrew instruction ultimately won out. And that was “one of the defining moments in the crystallization of the Israeli cultural identity,” according to “War of the Languages: Founding of the Technion/Technikum,” a special exhibition at the Haifa City Museum last spring and summer.

In the 1930s, finances were so tight that the Technion staff voted to work temporarily without pay rather than close down the school. During those pre-state years and especially during the War of Independence, the Technion was an active center for the Jewish underground and a source of crucial technological defense solutions. Many refugee scientists from Nazi-occupied lands found a place at the institute.

Once the war was over, the Technion began to boom in response to newborn Israel’s many development needs. It moved to a larger campus, and throughout the 1950s kept expanding its course offerings for a rapidly growing student body, including a medical school.

During the 1960s, the school’s reputation started attracting hundreds of students from developing countries in Africa and Asia. The Soviet Jewish immigration of the 1990s added about 1,000 more students to the population. New buildings were added to the campus, including the Henry and Marilyn Taub and Family Science and Technology Center, which boasts the Western world's largest computer science faculty. In 1998, Technion students designed, built and launched a microsatellite. Only five other universities have ever pulled off such a feat.

Over the years, scores of Technion faculty members have provided technological assistance to various countries under the auspices of the Foreign Ministry’s MASHAV Agency for International Development Cooperation as well as United Nations agencies.

The Taub Science and Technology Center at the Technion

boasts the Western world's largest computer science faculty

“When so many qualities, skills and ideas are concentrated together, it is an exhilarating experience,” stated Technion president Peretz Lavie following last summer’s annual board of governors meeting, which was devoted to marking the cornerstone centennial. “Whether in the ability to structure ideas, the courage to dream, or sensitivity to future need, the Technion family is alive with talent, which is a veritable resource to Israel and our shared future.”