By Rivka Borochov

Amir Yechieli, 61, high school teacher and founder of

Yevul Mayim in Jerusalem, was the first person to develop large-scale rooftop rain collection systems in Israel. He got the idea 15 years ago, just after a catastrophic flood wiped out a retaining wall of a Jerusalem school.

Even though it only rains in Israel during fall and winter, Yechieli’s work has not gone through a dry spell. In demand in Israel and Africa, this Israeli rain catcher is impacting the world one drop at a time.

In Israel alone, he manages to save about 100 days of water use a year at the schools where 120 of his systems are in operation. The rainwater is recycled to flush toilets or to provide drinking water.

How much the “average school saves every year depends on so many variables as well as how well the system is maintained,” he says.

Yevul Mayim builds rain catchers for schools, homes and for a village in Africa.

So basic and enterprising is his approach that international groups like the Rotary Club and the Jewish National Fund (JNF) have given Yechieli funding to devise more rain-collection systems.

Helping the largest east African university save water

The JNF is contributing toward Yechieli’s trip to Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda, where he believes installing a $30,000 rainwater conservation system can cut the university’s $15,000-a-month water bill to a fraction of that amount.

There is ample water in Uganda, but the problem is cleaning it for human use. The Yevul Mayim system collects rainwater from roofs and funnels it to a series of small drums where particulate matter is siphoned off.

Keeping things small and simple is the key, says Yechieli, citing support for why other international projects to catch and reuse rainwater have failed. Large drums are expensive, costing up to $150,000.

Yechieli has already installed a project in Kenya for a village of 600 people.

A similar project in Haiti is planned next. “They have no water to drink at a school there,” he says.

Paying it forward with the cost of water

In Israel, Yechieli, father of two girls, makes his living by working as a science teacher by day. He earns a modest fee for the installations he develops at schools, and goes out of his way, without a fee, to teach the schoolchildren how to use it, and to monitor water savings over time.

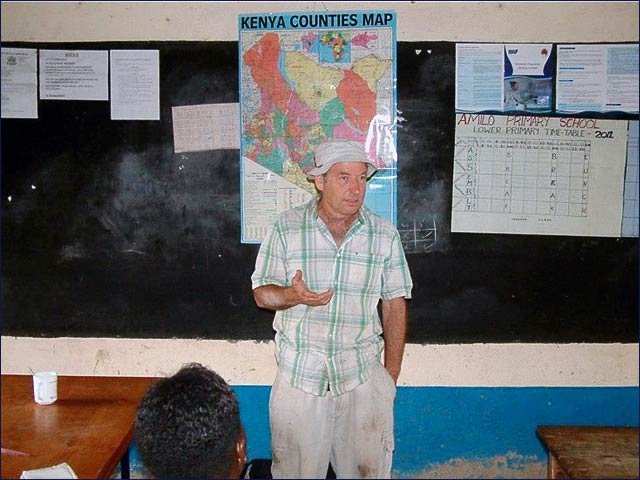

Amir Yechieli explaining the system in Kenya This way, conserving water isn’t a punishment; it’s an interactive school project that interests and engages the students, he says. It’s an especially good way to get kids from Arab and Jewish schools to start talking and working together. He has such a project ongoing between an Arab-Israeli school in Lod and a Jewish-Israeli school in Holon.

“It’s a pivotal subject in order for them to have a dialogue. It’s about water issues and environmental issues, and they do the same project in both schools to create a common goal.”

Business is flowing by “word of mouth,” he says. “The principals of the school are telling each other. So when a project comes to a close at a school and there is a body of students running it, I move onto another school.”