By Avigayil Kadesh

Yossi Kabessa, a 33-year-old applied physics PhD candidate from Israel, won the $100,000 Singapore Challenge 2014 at the Global Young Scientists Summit in Singapore (GYSS) for his project using genetically engineered bacteria to detect pollutants and hazardous materials in municipal water systems.

In an interview at Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Peter Brojde Center for Innovative Engineering and Computer Science, Kabessa says the futuristic notion began with a related project to use genetically engineered bacteria to detect explosives. This project is led by his faculty adviser, Prof. Aharon Agranat, and Prof. Shimshon Belkin.

“We’re working on an interesting project with the Ministry of Defense aiming to map buried landmines using this bacterial biosensor. If you spread the bacteria on a minefield, they will sense explosives, and an airborne vehicle will detect the optical signal they produce.”

Kabessa suspected these “designer” bacteria could also detect pollutants in large water systems. As the university’s Bryant and Lillian Shiller Fellow, he has been working to design the proper optoelectronics for such a scheme.

“The truth is, I didn’t do all this work alone,” says the father of four. “Prof. Agranat had the basic idea and gave me so many tools to work with. And there are very talented students in the lab who helped me in all levels of the project.”

This is why Kabessa is funneling his $100,000 prize back into the project. “I thought the right thing to do is to invest this money to further develop the idea. I believe that everyone gets what he deserves, and I had to think whether this money was really mine.”

A shining moment for Israel

Competition in the Singapore Challenge was formidable. The GYSS is a five-day program where bright young researchers meet with eminent scientists to discuss technologically innovative solutions to global challenges. The 10 proposals judged most promising get to vie for the cash prize.

Kabessa explains that scientists have known about engineered bacteria for about 15 years, “but using it for detecting pollutants in water is what is new. No one had harnessed engineered bacteria for an application like this.”

He was surprised to find fellow Israelis at the GYSS.

“There were four other students from Hebrew University, whom I had never met, but I was the only one from the physics department. There were also students from the Technion, the Weizmann [Institute of Science], Ben-Gurion University and Tel Aviv University,” Kabessa says.

“What’s interesting is that five of the 10 finalists were from Singapore, one was from France, one from Germany and three from Israel. That is quite a remarkable achievement, considering there were students from MIT, Cambridge, Harvard -- the best universities.”

A microscopic menorah

The Singapore Challenge win was the second time Kabessa’s name was in the Israeli news over as many months.

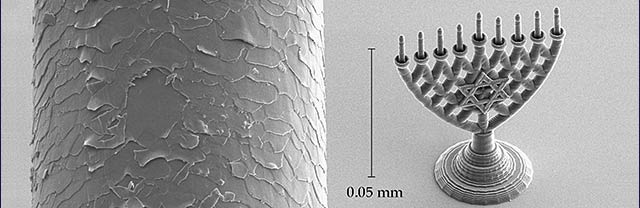

In December 2013, the religiously observant scientist shared photos of the world’s smallest Hanukah menorah that he and fellow doctoral student Ido Eisenberg fashioned in the lab out of a bit of polymer too small for the naked eye to see. They used a German-made 3D microprinter called the Nanoscribe – the first one in Israel and one of only about 100 globally.

“When we got the Nanoscribe system, we wanted to do a test to investigate its abilities … because 3D nanometric photography is brand new,” he explains. “People haven’t yet thought of what to do with it. We are just now trying to think out of the box to do something that nobody could do before.”

As Hanukah was coming up, the scientists decided that an eight-branch candelabrum would be an appropriate form with which to experiment. “We were amazed at the results -- so clean and clear on a scale of a speck of dust,” he says, adding with a smile, “Perhaps next year we’ll light it with quantum particles!”

The Nanoscribe will help Kabessa turn his award-winning biosensor into a micro lab on a chip, including all the optics and electronics and sensors that go inside it.

Kabessa’s Hanukah menorah cannot be seen with the naked eye

Kabessa’s Hanukah menorah cannot be seen with the naked eye

How does that work?

Kabessa recalls that when he was a boy, he wondered about the mechanisms behind the seemingly magical ability to warm food by pushing buttons on a microwave, or turning on the car with the crank of a key.

Though he was initially planning to study psychology after his army service, “I was very curious about the laws of nature and everything around us, and it drove me to go into physics or electrical engineering.”

With a bachelor’s degree in physics, he decided to go for a master’s in applied physics after hearing Agranat lecture on this discipline.

“The things he talked about were so inspiring and interesting, such an integrated vision of the technology and the direction it should go. I went to talk to him and asked if there was a place for me [in his department],” Kabessa recalls.

Agranat suggested the biosensor project, and the rest is history.