The Bedouin in the Negev, numbering approximately 210,000, is one of many communities which comprise Israel's pluralistic society. Unfortunately, historically this community has been ranked low in socio-economic indicators.

Recognizing that the Bedouin of the Negev need assistance, the government of Israel created a comprehensive policy - called the Begin Plan - aimed at improving their economic, social and living conditions, as well as resolving long-standing land issues.

To this end, Israel has allocated approximately 2.2 billion dollars (8 billion shekels), including over 330 million dollars (1.2 billion shekels) for specific economic and social development projects.

This

January 2013 policy - named after then-minister Ze'ev Binyamin (Benny) Begin - is designed to solve a wide range of problems affecting the Bedouin population. Among the numerous initiatives that have begun or are planned are the expansion of technological and adult education, the development of industrial centers, the establishment of employment guidance centers, assistance in strengthening Bedouin local governments, improvements to the transportation system, centers of excellence for students and support for

Bedouin women who wish to work or start businesses.

Ahmed Al-Karnawi in his greenhouse in Rahat in the NegevAs

part of the Israeli government's efforts to reduce Bedouin

unemployment, he and other Bedouin have received government plots to set

up agricultural businesses. Al-Karnawi cultivates roses (which

he exports abroad) and vegetables. (Copyright: MFA free usage)

Ahmed Al-Karnawi in his greenhouse in Rahat in the NegevAs

part of the Israeli government's efforts to reduce Bedouin

unemployment, he and other Bedouin have received government plots to set

up agricultural businesses. Al-Karnawi cultivates roses (which

he exports abroad) and vegetables. (Copyright: MFA free usage)Israel is working with the Bedouin community on all aspects of the Begin Plan. Indeed, the plan was developed through dialogue and in close coordination with the Bedouin: In an attempt to expand on the previous Prawer Plan, Minister Begin and his team met with thousands of Bedouin individuals and organizations during the development stage. As a result, Bedouin traditions and cultural sensitivities were taken into consideration, and a plan was formulated to reinforce the connection of the Bedouin to their culture and heritage.

Furthermore, contrary to some claims, Israel is not forcing a nomadic community to change its lifestyle. The Bedouin in the Negev, who moved to the area starting at the end of the 18th century, began settling down over a hundred years ago, long before the establishment of the State of Israel. By now, most Bedouin citizens live in permanent homes.

Still, one of the major problems facing the Bedouin is housing. Almost half of the Negev Bedouin (approximately 90,000) live in houses built illegally, many of them in shacks without basic services. Isolated encampments and other Bedouin homes may lack essential infrastructures, including sewage systems and electricity, and access to services such as educational and health facilities is limited.

There are solutions to this problem and to the many other difficulties facing the Bedouin. For example, under the Begin Plan, the government is giving every Bedouin family (or eligible individual) that needs it, a resident plot. These lands are being developed to include all the modern infrastructures and will be granted free of charge. Bedouin families can then build houses according to their own desires and traditions. Those that move will be offered their choice of joining rural, agricultural, communal, suburban or urban communities.

A street in the Bedouin village of Drijat, "the first Bedouin solar village"

The village was converted in 2005 to a modern solar village by a governmental project of a multipurpose solar electricity system. Thus, many houses, the school, the mosque and the street lights in Drijat are powered by solar panels. (Copyright: MFA free usage)

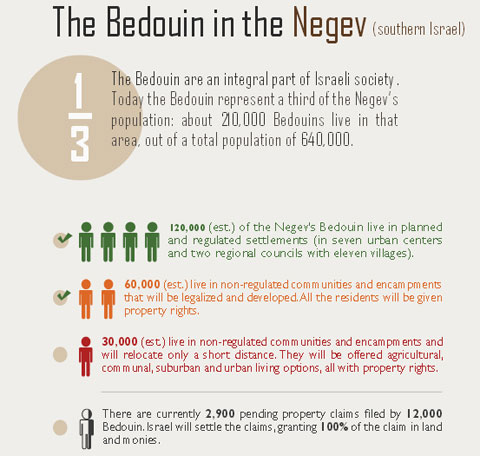

Most of the Bedouin citizens will remain in their current homes. 120,000 already live in one of the seven Bedouin urban centers or eleven recognized villages. Of the remaining 90,000 that live in encampments or communities that are not zoned, only 30,000 will have to move, most of them a short distance (a few kilometers at most). The other 60,000 will have their homes legalized under Israel's initiative, which will develop their communities and grant the residents property rights.

Much has been made of those Bedouin who will have to move. However, almost half of them (14,000-15,000) have settled illegally within the danger zone of the Ramat Hovav Toxic Waste Disposal Facility. Given the threat to their health, and even lives should there be an incident at the facility, the government of Israel has an obligation to relocate these families.

The Begin Plan will also resolve land claims made by a number of Bedouin in the Negev, most of which have been in dispute for decades. Currently, there are 2,900 land claims regarding 587 square kilometers (227 sq. miles). Although these claims have no legal basis under Israeli law (and were not recognized under the previous Ottoman or British land law systems), Israel wants to resolve the issue. It will do so by adopting a compromise according to which all the Bedouin claimants will receive compensation in land and money equivalent to the full value of the land claimed. The Bedouin will no longer have to engage in lengthy court cases while the compensation process will be based on the principles of fairness, transparency and dialogue

There have been attempts to attack the Begin Plan (which its detractors

deliberately misname the Prawer Plan in order to associate it with an outdated proposal). Many of those acting in the international arena against Israel's plan for the Bedouin belong to the camp which seizes upon any opportunity to harm Israel's reputation. Others have purer motives, but have based their opposition on false information distributed by Israel's opponents.

This opposition is unfortunate, particularly for the Bedouin who will benefit greatly from the Begin Plan. This new policy constitutes a major step forward towards integrating the Bedouin more fully into Israel's multicultural society, while still preserving their unique culture and heritage.

Most importantly, the Begin Plan guarantees a better future for Bedouin children. No longer will they have to reside in isolated shacks without electricity or proper sewage. Now they will live closer to schools and will be able to walk home safely on sidewalks with streetlights, alongside paved roads. They will have easier access to health clinics and educational opportunities. Their parents will enjoy greater employment prospects, bettering the economic situation of the whole family. To oppose the Begin Plan is to oppose improving the lives of Bedouin children.

A classroom in the Regional

Center for Education and Rehabilitation of Disabled Bedouin Children

(suffering from C.P.) in the town of Tel Sheva in the Negev. The center,

financed by Israeli governmental ministries, currently accommodates

around 140 children with C.P., from pre-kindergarten to post

high-school age, and will in the future accommodate 500 pupils.

(Copyright: MFA free usage)

A classroom in the Regional

Center for Education and Rehabilitation of Disabled Bedouin Children

(suffering from C.P.) in the town of Tel Sheva in the Negev. The center,

financed by Israeli governmental ministries, currently accommodates

around 140 children with C.P., from pre-kindergarten to post

high-school age, and will in the future accommodate 500 pupils.

(Copyright: MFA free usage)